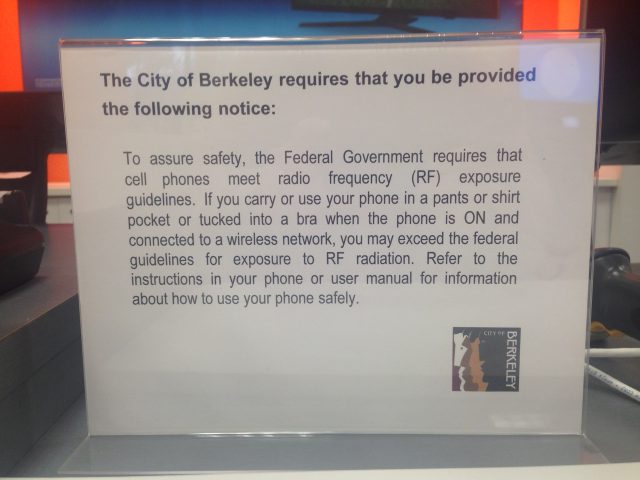

That law went into effect earlier this year after the cell phone trade group sued to halt it. Earlier this year, a federal judge ruled in favor of the defendants in CTIA v. City of Berkeley, allowing a municipal ordinance to stand, with one small revision.

The Cellular Telephone Industries Association (CTIA), meanwhile, has argued that this violates the industry’s First Amendment rights, as it compels speech. “This is confusing,” Ted Olson, a former solicitor general under the George W. Bush administration, argued before the 9th Circuit on behalf of CTIA. “What the [Federal Communications Commission] says, your honors, with respect to its findings of cell phones used in the US is that they are safe. What Berkeley's message says is: ‘Watch out!’”

Olson, who previously made similar arguments before the US District Court level, repeated his claim that this government-required notice was a “burden on speech.”

“There’s a reason why Berkeley put the word ‘safety’ in there, it’s to send an alarm,” he said.

“Our position is that we are relying on a regulation of the FCC,” he told the 9th Circuit. “We don’t want to get into an argument about the science, we don’t think we should have to. The standard of review should be that we should have a rational basis of review.”

Specifically, one of the primary ways that radiation from a phone is measured is through something called the Specific Absorption Rate (SAR)—in other words, how fast a given amount of energy is absorbed by the human body, measured in watts per kilogram.

Since 1996, the FCC has required that all cell phones sold in the United States not exceed a SAR limit of 1.6 watts per kilogram (W/kg), as averaged over one gram of tissue. On most phones, it’s not at all obvious what the SAR value for a given handset is. On the iPhone 6S Plus—the author’s phone—for instance, the information is buried four menus deep, and even then requires clicking yet another link.

Back in 2010, the city and county of San Francisco passed a similar ordinance that required retailers to provide the SAR value for each display phone and related printed literature as to what that SAR value means. The ordinance, which was signed into law by then-Mayor Gavin Newsom, would have imposed a fine of $500 for each violation. The CTIA sued over that law and eventually prevailed at the 9th Circuit—San Francisco gave up after that.

Berkeley’s law is much narrower and less burdensome than San Francisco's.

What does “safe” mean, anyway?

“I also think it is a fair inference from when the language starts out to assure safety, that if you don’t do this, it might well be unsafe. The question is one of tone or implication,” Judge Fletcher said. “I read that language to say: ‘Uh oh, I’m in trouble if I put it in my pocket.’”

He also pointed out early on, as Ars noted in May 2016, that a new $25 million, years-long US government study had finally found a clear connection between cell phone radiation and tumors in rats—striking fear in the hearts of gadget lovers worldwide. However, Judge Fletcher did not mention what Ars further reported: that this study was full of red flags and shouldn’t be viewed as fully conclusive. Large and comprehensive works indicate that any potential risks take decades to be felt, and cell phones simply haven't been in use long enough for us to know for sure.

The other judges did not obviously indicate how they might be leaning.

As Ars also reported previously, it's important to note that there really isn’t any current science to support the need for the warnings Berkeley is mandating. There's no well-described mechanism by which non-ionizing radiation can induce long-term biological changes, although it can cause short-term heating of tissues. There are also no clear indications that wireless hardware creates any health risks in the first place, which raises questions of what, exactly, the city's legislation was supposed to accomplish.

Following the conclusion of the hearing, Olson declined to take questions from reporters outside the courthouse. Lessig, for his part, took a few questions.

“Our view was that it’s important that jurisdictions have the ability to regulate without requiring a huge factual finding, spending tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in order to support the regulation,” Lessig said.

“I’ve always said this case is not about the science. It’s about the ability of a government to issue safety warnings without bearing this incredible burden that typically happens when you try to restrict somebody’s speech. That’s why the case, our brief says: what this case is really about is, you can think of it as a multinational corporate veto on the right of a city to regulate. Because if cities like Berkeley fear that they’re going to have a lawsuit funded by a multinational corporation against them every time they have a safety warning—they will just stop having safety warnings. Because they can’t afford to be litigating First Amendment cases every time they want to say something might be unsafe.”

The court is expected to rule within the coming months.

for extended reading: http://bit.ly/2csK0mk