Non-Thermal Effects Hang in the Balance

Repacholi’s Legacy of Industry Cronyism

After eight years of work, the World Health Organization (WHO) is reopening its review of the health effects of RF radiation for a summary report intended to serve as a benchmark for its more than 150 member countries. The report will be used as a guide to respond to widespread concerns over the new world of 5G.

The WHO issued a public call in October for detailed literature reviews on ten types of RF–health impacts from cancer to fertility to electrohypersensitivity. Some see the move as a sign that the health agency is interested in opinions beyond those of its long-time partner, the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP). They hope that the WHO is finally ready to recognize evidence of low-level effects, in particular the link between cell phones and cancer. Others are far from convinced.

The skeptics see the new reviews as little more than a ruse. They fear that the WHO is only going through the motions and will in the end stick with ICNIRP’s long-held position that there are no RF effects other than those caused by heating.

Tight Schedule for the Systematic Reviews

The RF report, formally known as an Environmental Health Criteria (EHC) monograph, was last updated in 1993, more than 25 years ago. The WHO Radiation Program, based in Geneva, started working on a revision in 2012 with a target completion date of 2016. Eleven chapters of the draft report were released for review in 2014, and work on a second draft got under way soon after public comments were received. After that the process stalled, and the RF EHC was stuck in limbo.

Then, in early October —after a long public silence— the WHO issued the call for those ten “systematic reviews.” Systematic review is a term of art —you can read about it in a WHO handbook that presents a step-by-step formula on how to develop a health guideline, such as an EHC. The short version is that a systematic review takes a lot of work. As someone who has completed a number of them put it, “It’s not a trivial matter.” Even responding to a call for a systematic review is not easy, he added.

Each team must include at least two individuals, and “geographical diversity” is encouraged. Teams for systematic reviews can have up to six members, sometimes more, according to the WHO handbook.

The WHO set a very tight schedule. Responses to the call for all ten reviews are due today, November 4. Applicants had less than a month to complete the paperwork —that is, if they heard about it right away. The call was not published anywhere or posted on the Internet. Rather, Emilie van Deventer, the team leader of the WHO radiation program, sent a notice to her mailing list. Though the call is dated September, no one I spoke to received it before October 8. Many heard about it second hand, as did I.

Van Deventer left out some of those best-placed to raise awareness of the call. Dariusz Leszczynski, a now-retired professor in Helsinki who was a member of the IARC RF–cancer assessment in 2011 and who runs a blog for the EMF/RF community, wasn’t on her list. “I learned of it by coincidence, surfing the Internet,” he told me. (He is not responding to the call.) Leszczynski posted the WHO announcement on October 9 and was one of the first to publicize it.

Also ignored was Joel Moskowitz, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, who writes another widely followed blog, Electromagnetic Radiation Safety. He, like Leszczynski, has been critical of ICNIRP’s thermal-only outlook.

“It’s very surprising that they set such a short deadline; it would discourage good, very busy people from participating,” said one long-time researcher, who may submit a proposal. “You can’t put an international team together overnight.”

(A ground rule: With a few exceptions, those interviewed about the WHO call asked for anonymity so that they could speak frankly without jeopardizing their chances of being selected.)

MicroSafe Cover Is The Best Protection From EMF Radiation ORDER IT HERE

A Fast Pace, But No Money

The pace does not ease up after the November 4 deadline. WHO officials have less than a month to evaluate the applications and make their selections. Work on the ten reviews must begin no later than December 2, and completed manuscripts submitted to an open-access, peer-reviewed journal within twelve months.

One more thing: There’s practically no money for the reviewers. WHO states that “only a small contribution towards the operating costs” will be available. In an e-mail exchange, van Deventer would not disclose the budget, saying only that there would likely not be enough money “to cover the total amount needed for a systematic review.”

According to the WHO handbook, members of a systematic review team “should have no financial or non-financial conflict of interest.” All applicants must submit a detailed declaration of interests, including income from employment, grants, consulting and investments.

The call states that each declaration “will be assessed for conflict of interests.” No one, apparently, will be automatically disqualified based on apparent conflicts, as was the case for IARC’s RF review in 2011 (more here; IARC is an agency of the WHO).

Who Picks? Why the Rush?

Most everyone I contacted was wondering, who will select the “winners”? When I posed the question to van Deventer, she replied the “WHO Secretariat,” adding that “rigorous internal processes” would be followed.

Even after they are picked, the identity of the winners will not be immediately revealed. Van Deventer said that she is not planning to announce the selections when the decisions are made. At the latest, we may not know who is preparing the reviews until they appear in print.

The other question on peoples’ minds was, “Why the big rush?” After all, work on the RF EHC began back in 2012; another month or two to give applicants more time would hardly make a difference.

In fact, EMF managers at the WHO knew years ago that systematic reviews would be required. That was part of new procedures for writing such documents, as set out in the WHO handbook. All van Deventer had to do was issue the call. She laid out what had to be done at an EMF Project advisory committee meeting in Geneva in late June 2017. She estimated that 15 reviews would be needed at a cost of $10-15,000 each. And, crucially, they “must be commissioned externally.” Even then, however, she did not have any money to pay for the reviews.

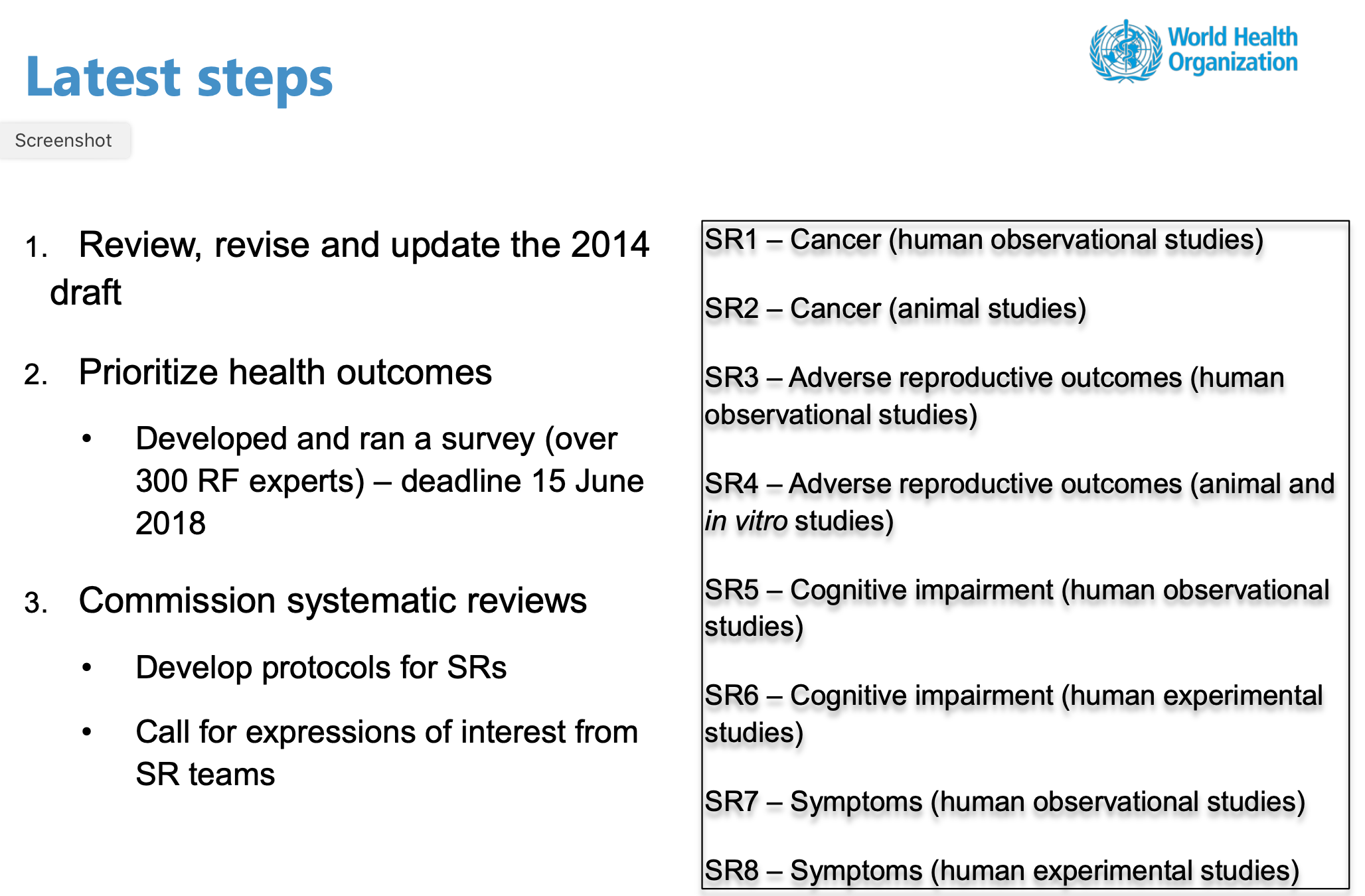

Over the last year, van Deventer regularly briefed the International Telecommunications Union on the RF EHC. The ITU, which is also part of the UN, is a public-private partnership with many government and corporate members. In each talk, van Deventer said that the WHO would go ahead to “review, revise and update the 2014 draft.” In May of this year, she said the ITU that she would commission eight systematic reviews (see slide* below); the list was later expanded to ten.

Slide No.25, E. van Deventer presentation to the ITU, most likely on May 20, 2019*

A few days earlier at the same ITU meeting, the Mobile and Wireless Forum, a trade association formerly known as the Mobile Manufacturers Forum, was invited to give a presentation on “Preparing for 5G: Research Relating to RF Exposure.”

E-mail traffic, shared with Microwave News, shows that van Deventer’s briefings were well circulated among ITU’s corporate members who follow the health question.

If van Deventer knew years ago that systematic reviews were needed, why did she wait until now to issue the call and then allow less than a month for replies? I asked her but she did not answer. I also asked the WHO press office to explain the rush. No one there replied or even acknowledged the request.

Also, why were telecom managers better briefed on the pending reviews than those in the health sciences who would be doing them?

Is the Call Rigged To Favor ICNIRP?

The lack of advance notice and the fast deadline have led some to question whether the WHO engineered the schedule to help ICNIRP stay in control. “I suspect that at least some have already been pre-selected to do the reviews,” said one European observer. “Even though it might seem to be an open and balanced approach,” commented another seasoned veteran, “I’m not convinced that in the end they won’t choose ICNIRP and Co.”

ICNIRP members would be well prepared to respond to the calls. They have recently finished their own literature reviews to update ICNIRP’s exposure guidelines, issued in 1998.

“The RF guidelines are now in press and publication is expected before the end of the year,” Eric van Rongen, the chairman of ICNIRP, told me in an e-mail exchange. In a presentation last April in Paris, van Rongen revealed that the exposure guidelines would continue to be based exclusively on thermal effects. There is “no evidence that RF EMF causes such diseases as cancer,” he said. Van Rongen is with the Health Council of the Netherlands.

Two important reviews by ICNIRP members have recently been published: one on epidemiological studies and the other on the NTP and Ramazzini animal studies. As von Rongen reaffirmed, neither indicates any movement towards accepting even the possibility of a RF–cancer risk.

WHO and ICNIRP’s Long, Intimate Association

From the very beginning, the WHO EMF Project and ICNIRP have been intertwined. This is not surprising since Michael Repacholi, an Australian biophysicist turned bureaucrat, was instrumental in setting up both organizations, ICNIRP in 1992 and the EMF Project four years later. (His bio is here, there’s a lot more below.)

From the very beginning, the EMF Project relied on ICNIRP for its scientific expertise, or in UN-speak, to serve as its scientific secretariat. In 2005, seven years before work on revising the RF EHC began, the WHO commissioned ICNIRP to do a review of the RF health literature, and Repacholi announced that the review would “serve as an input” for the RF EHC. It was completed in 2008.

Rick Saunders and van Rongen, then an ICNIRP member and advisor, respectively, were asked to help the WHO guide the EHC “to its completion.”

WHO’s Emilie van Deventer ICNIRP’s Eric van Rongen

Work on the RF EHC formally began at a meeting in Geneva in January 2012. The EHC would be based in part on ICNIRP’s literature review, according to the EMF Project’s 2012-2013 annual report. A “core group” was established to help develop the EHC. Five of its six members† had close ties to ICNIRP. Van Rongen, who by then had joined the Commission, was in the core group. (He became the chairman of ICNIRP in May 2016.)

That core group, with the help of a couple dozen advisers, drafted the 11 chapters that were released for public comment in 2014.

A Contentious Meeting in Geneva

The draft got a stormy reception. There were 686 comments in all, and a good many criticized the WHO for discounting low-level, non-thermal effects. The WHO has not released the comments, preventing a count of pros and cons.

Later, in a widely circulated letter sent to Maria Neira, the WHO executive in charge, Oleg Grigoriev, the chairman of the Russian national non-ionizing radiation committee, complained that the core group that drafted the report was “not balanced and [did] not represent the point of view of [a] majority [of the] scientific community studying [the] effects of RF.” He and others were disappointed that the WHO had failed to go beyond the heat-only dogma embraced by ICNIRP.

On March 3, 2017, at about the same time that Grigoriev’s letter landed on Neira’s desk in Geneva, she and van Deventer hosted a five-member delegation from the European Cancer and Environment Research Institute. They were there to deliver the same message: The RF EHC should include low-level effects.

Maria Neira Lennart Hardell

The meeting did not go well. Neira rebuffed their overture and rejected any type of collaboration. She went on to tell them that they should not expect any future meetings, according to a brief account by Sweden’s Lennart Hardell, a member of the ECERI delegation.‡

Neira did not respond to a request for comment.

The five researchers went home and laid out their case in a paper that was published in the journal Environmental Pollution last year. This is their bottom line:

“It is urgent that national and international bodies, particularly the WHO, take this significant public health hazard seriously and make appropriate recommendations for protective measures to reduce exposures.”

After that, little more was said about the RF EHC document —at least in public— as van Deventer and others looked for a way to comply with the new WHO rules that required systematic reviews, compounded by an added protocol for working with non-government organizations (NGOs, for instance, ICNIRP). WHO’s Engagement with Non-State Actors, better known as FENSA, was issued in 2016.

These changes were raised at that same EMF Project advisory committee meeting held in June 2017, close to four months after Neira met with the non-thermalists. Van Deventer explained to the group that, “FENSA potentially makes co-publication of the [RF EHC monograph] with ICNIRP problematic.” She went on to explain:

″A[nother] question concerned cooperation with ICNIRP in the development of the EHC. The WHO Guideline Development process would permit this provided the required processes were followed. However, it is not clear whether this is possible with the introduction of the new FENSA.”

The minutes of the meeting show that an attendee, who is not named, warned: “There may be dangers in aligning WHO with ICNIRP and cooperating with them will not make the guidelines better.”

With van Deventer no longer responding to my e-mails, I turned to van Rongen. He told me that there had been discussion of the constraints of the new WHO rules for developing guidelines and working with NGOs, and then he added,

“[There] was concern on the personal involvement of several members of the Core Group who are also members of the Main Commission of ICNIRP (myself, Maria Feychting, Gunnhild Oftedal) and several other experts who are assisting the Core Group and who are either Commission members or members of the Scientific Expert Group of ICNIRP.”

Investigate Europe on WHO & ICNIRP

Last March, the WHO was pressured from a different direction: An international team of journalists, working under the banner “Investigate Europe,” published a series of articles in newspapers across the continent on the national and multinational groups that set EMF/RF policy. They focused on the WHO EMF Project and ICNIRP.

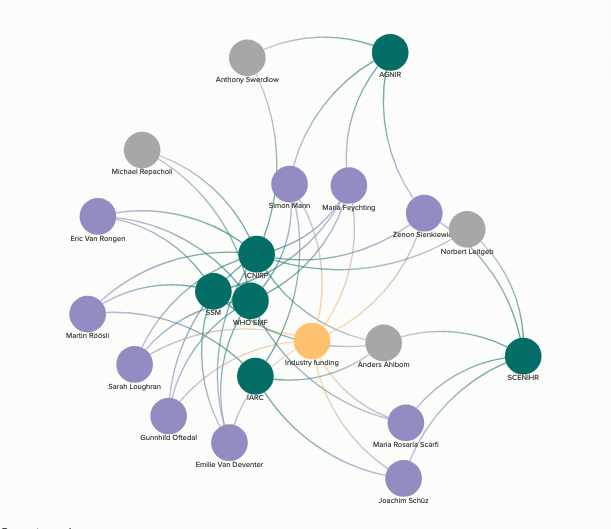

Investigate Europe put together an interactive graphic showing six key organizations (in green, with WHO and ICNIRP at the center, below) and their links to important players and sources of industry funding. Some of the journalists referred to ICNIRP as a “cartel.”

Source: Investigate Europe

Source: Investigate Europe

In an overview article, titled “How Much Is Safe?,” the team described how allegations of one-sidedness had “ravaged” the core group of ICNIRP insiders who drafted the chapters of the EHC report that were released in 2014.

When the journalists turned to the WHO for comment last December, a spokesperson “assured” them that the agency would put together a larger panel to “evaluate” the work of the original core group. The new participants would include “a broad spectrum of opinions and expertise,” according to the WHO.

The press office was referring to a Task Group that would take the draft chapters and complete the RF EHC. Despite years of being on the brink of appointing members, van Deventer has yet to assemble the group. Van Rongen told me that she has recently identified someone to chair it but he was not at liberty to reveal who it is.

WHO, ICNIRP & Michael Repacholi

Much of the suspicion over WHO’s handling of the RF EHC can be traced back to Michael Repacholi and his legacy of cronyism and favoritism to industry.

Repacholi, the former head of both the EMF Project and ICNIRP, was a leading player in the writing of WHO EHC reports on EMFs, at both high and low frequencies, for close to 30 years.

Back in 1981, while working for Health and Welfare Canada, he was on the committee that issued the first RF EHC (#16). An update (#137) came out in 1993 with Repacholi, who by then was back home in Australia, serving as the chairman of the panel. Three years later, he was in Geneva to open and run the EMF Project, where he stayed until he retired in 2007. Before he left, Repacholi shepherded an EHC report (#238) on ELF (power frequency) EMFs through the WHO bureaucracy.

Michael Repacholi ELF EHC 2007

Financial disclosure was never a priority for Repacholi, and details of the WHO Project’s budget and funding were closely held. Even when the cell phone industry admitted that it was making annual, six-figure contributions to the WHO EMF project, Repacholi kept it all very hazy.

ICNIRP’s finances are no more transparent.

Repacholi retired from the WHO in 2006 and immediately became an industry consultant. On his first outing, he was accused of misrepresenting the as-yet-unreleased ELF EHC report for the benefit of his corporate clients. (See our story, his response, and our reply.)

Later, stating that he wanted to “set the record straight,” Repacholi revealed that half of the WHO EMF Project funding had come from industry.

Taking money from Motorola and industry trade associations, among others, violated WHO rules. Repacholi found a work-around bypassing —laundering— the money through the Royal Adelaide Hospital in Australia, where he had been a chief scientist from 1983 to 1991. The WHO turned a blind eye and cashed the checks. The industry was rewarded with a seat at the WHO table.

One of the ironies of Repacholi’s career is that, in the mid-1990s, he led one of the first animal studies to link cell phone radiation to cancer. In stunning disregard for public health, Repacholi kept the results secret for two years, telling only Telstra, the Australian telecom giant that paid for the study. (Our write-up is here.) There have been two attempts to repeat the experiment, but both were botched, and his finding stands.

source: https://bit.ly/2NGn3il